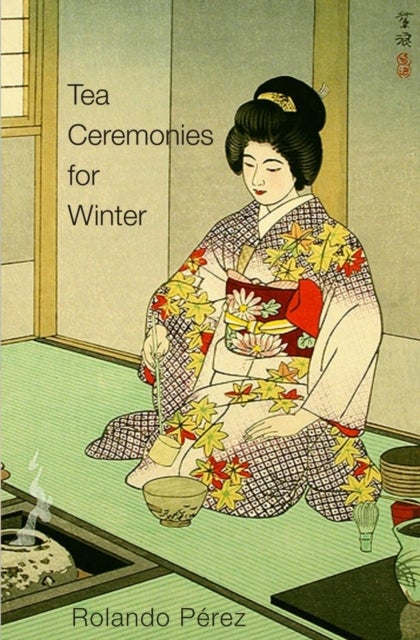

Tea Ceremonies for Winter av Pe&#769, Rolando rez

199,-

<p>The Japanese tea ceremony is an attempt to impart meaning to that which would oth- erwise go unnoticed. After all, what is so different about serving, pouring, drinking tea, than the brushing of one’s teeth? No-thing. What gives significance to the serving of the tea is the “ceremony” itself—that is, the form. For in the tea ceremony, the form is the content. Now, in comparison to the Western poem, “full of” meaning, allusions, mythologies, history, etc. a haiku may “just” describe a scene in nature: the landscape: a river, a tree, a bird, and not much else. But that is so very much already, Rolando Pérez seems to suggest in <em>Tea Ceremonies for Winter</em>. So very much. “The objects of nature pre- sented in a Basho haiku, for instance, simply are—they exist for themselves,” says Pérez. “If they are ‘sublime,’ they are not so for us,” and this is what we must all learn, if we a