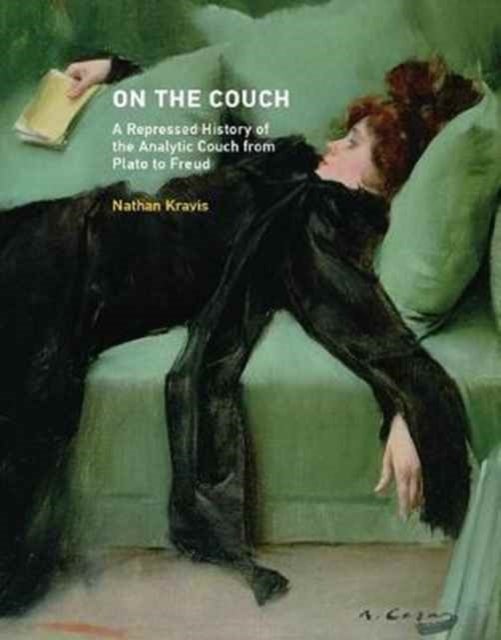

On the Couch av Nathan (Doctor) Kravis

379,-

<b>How the couch became an icon of self-knowledge and self-reflection as well as a site for pleasure, transgression, and healing.</b><p>The peculiar arrangement of the psychoanalyst''s office for an analytic session seems inexplicable. The analyst sits in a chair out of sight while the patient lies on a couch facing away. It has been this way since Freud, although, as Nathan Kravis points out in <i>On the Couch</i>, this practice is grounded more in the cultural history of reclining posture than in empirical research. Kravis, himself a practicing psychoanalyst, shows that the tradition of recumbent speech wasn''t dreamed up by Freud but can be traced back to ancient Greece, where guests reclined on couches at the <i>symposion</i> (a gathering for upper-class males to discuss philosophy and drink wine), and to the Roman <i>convivium</i> (a banquet at which men and women reclined together). From bed to bench to settee to chaise-longue to sofa: Kravis tells how the couch became an icon of