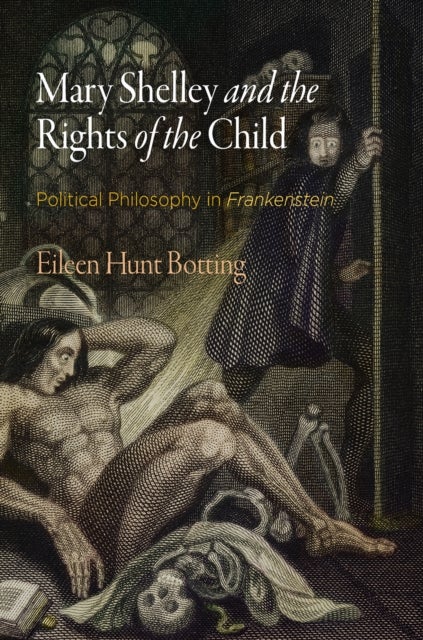

Mary Shelley and the Rights of the Child av Eileen M. Hunt

423,-

<p>From her youth, Mary Shelley immersed herself in the social contract tradition, particularly the educational and political theories of John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, as well as the radical philosophies of her parents, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and the anarchist William Godwin. Against this background, Shelley wrote <i>Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus</i>, first published in 1818. In the two centuries since, her masterpiece has been celebrated as a Gothic classic and its symbolic resonance has driven the global success of its publication, translation, and adaptation in theater, film, art, and literature. However, in <i>Mary Shelley and the Rights of the Child</i>, Eileen Hunt Botting argues that <i>Frankenstein</i> is more than an original and paradigmatic work of science fiction—it is a profound reflection on a radical moral and political question: do children have rights?<br/>Botting contends that <i>Frankenstein</i> invites its readers to reason through