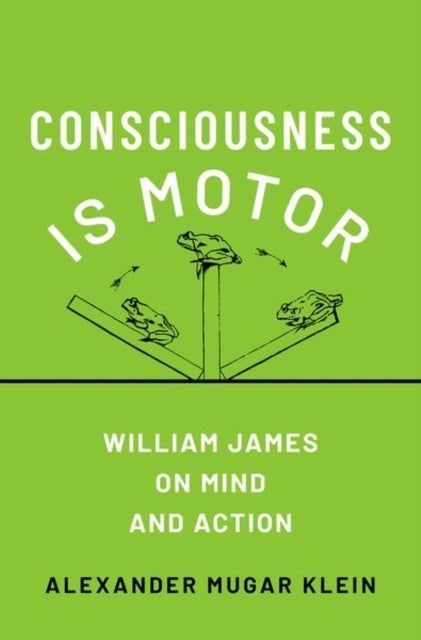

Consciousness is Motor av Alexander Mugar (Canada Research Chair and Associate Professor Canada Research Chair and Associate Professor McMaster Univer

799,-

William James was an acknowledged master of phenomenal description. He gave us the "stream of consciousness" that "flows," and the newborn's mental life as a "blooming, buzzing confusion." But in Consciousness Is Motor, Alexander Klein shows that James sculpted these phenomenal descriptions around an armature of empirical details. His book reconstructs James's models of consciousness and volition, uncovering results from animal experimentation and clinical observation on which those models were built. What emerges is a more powerful and more empirically-informed account of mind than has been appreciated. James's early work on consciousness engaged the 1870s automatism controversy. The controversy was triggered, Klein argues, by experiments demonstrating that living, decapitated frogs are capable of goal-directed action. One side regarded goal-directedness as evidence of spinal consciousness; the other espoused epiphenomenalism, reasoning that consciousness must play no role in producin